Functional Programming - part 3

Immutability in Functional Programming

In this continuation of posts on functional programming, I aim to dive deeper into the code and implement the discussed concepts in the world of programming. The goal of this section is to refactor existing code into an immutable architecture. We previously discussed immutability, so let’s start by redefining a few key terms to ensure clarity.

Definitions

- Immutability: The inability to modify data.

- State: Data that changes over time.

- Side Effect: A change that occurs in the data.

In the code snippet below, I have tried to illustrate the difference between a Stateless class and a Stateful one.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

// Stateful

public class UserProfile

{

private User _user;

private string _address;

public void UpdateUser(int userId, string name)

{

_user = new User(userId, name);

}

}

// Stateless

public class User

{

public User(int id, string name)

{

Id = id;

Name = name;

}

public int Id { get; }

public string Name { get; }

}

Why is Immutability Important?

Every mutable operation is equivalent to unclear code. In fact, the dependency of every action on state introduces instability into the code. For instance, imagine a multithreaded operation where several threads simultaneously alter the state. Managing this would lead to unreadable code and increase complexity.

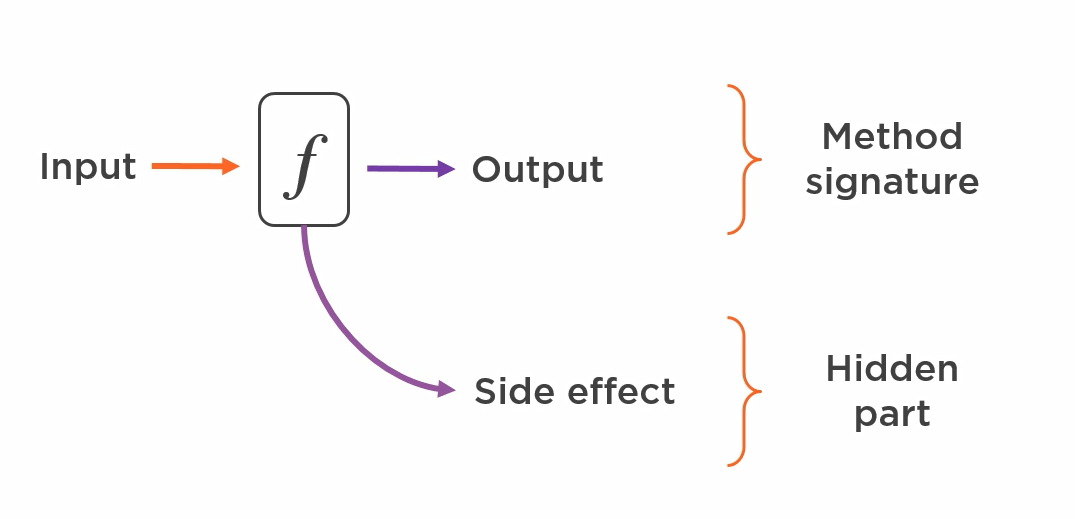

Ideally, for a given input, the method body should return a consistent output. However, in reality, the impact that method execution has on the state of the entire class is hidden from us, which can lead to future problems.

Let’s rewrite the code above to make it more honest:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

public class UserProfile

{

private readonly User _user;

private readonly string _address;

public UserProfile(User user, string address)

{

_user = user;

_address = address;

}

public UserProfile UpdateUser(int userId, string name)

{

var newUser = new User(userId, name);

return new UserProfile(newUser, _address);

}

}

public class User

{

public User(int id, string name)

{

Id = id;

Name = name;

}

public int Id { get; }

public string Name { get; }

}

In this example, the UpdateUser method now returns an instance of the UserProfile class, rather than void. The UserProfile class, in turn, requires a User object and an address to instantiate, ensuring they are properly initialized. Another important note here is that each method call returns a new object, without being dependent on the instantiation of other objects.

How Immutability Benefits Us:

- Improved Code Readability: The code becomes easier to understand and maintain.

- Centralized Validation: We have one clear place to validate the object’s integrity.

- Thread-Safety: Immutability inherently provides thread safety.

However, working with immutable objects has some drawbacks, such as increased memory and CPU usage. Since objects are never mutated, more objects will be created in the process. In the .NET, there are optimizations for working with immutable objects, such as the ImmutableList class, which reduces overhead and minimizes the burden on garbage collection (GC).

Example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

// Create Immutable List

ImmutableList<string> list = ImmutableList.Create<string>();

ImmutableList<string> list2 = list.Add("Salam");

// Builder

ImmutableList<string>.Builder builder = ImmutableList.CreateBuilder<string>();

builder.Add("first");

builder.Add("second");

builder.Add("third");

ImmutableList<string> immutableList = builder.ToImmutable();

How to Deal with Side Effects?

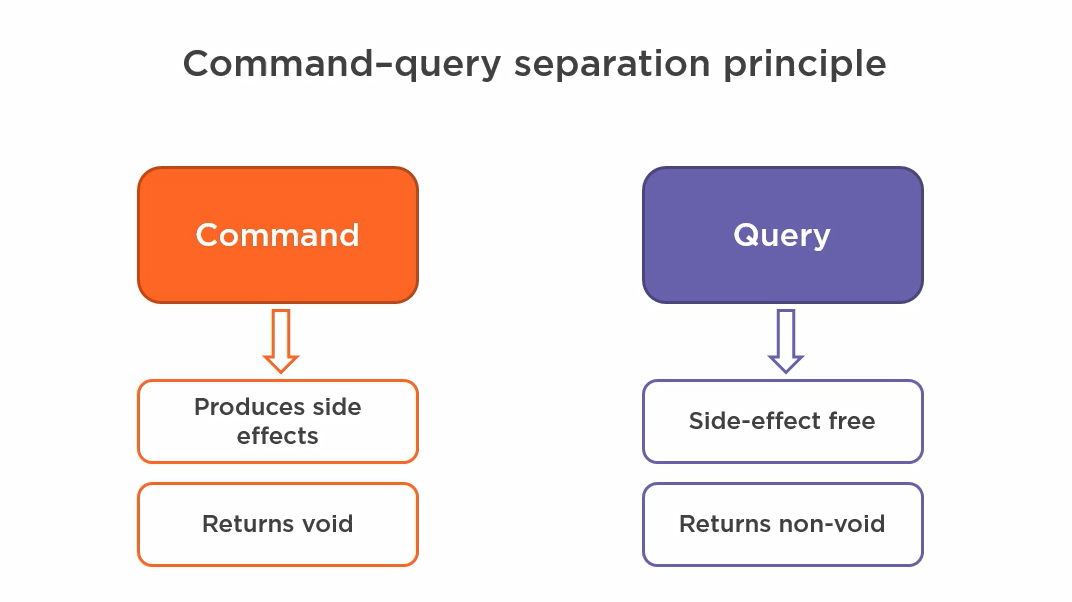

A common pattern for managing side effects is the Command/Query Separation principle. Simply put, we consider all operations that produce side effects as Commands, which generally return nothing, and Queries, which return data without altering the system’s state.

A common misconception about this pattern is limiting it to specific architectures like Domain-Driven Design (DDD), but there is no strict requirement to adhere to it in other architectures.

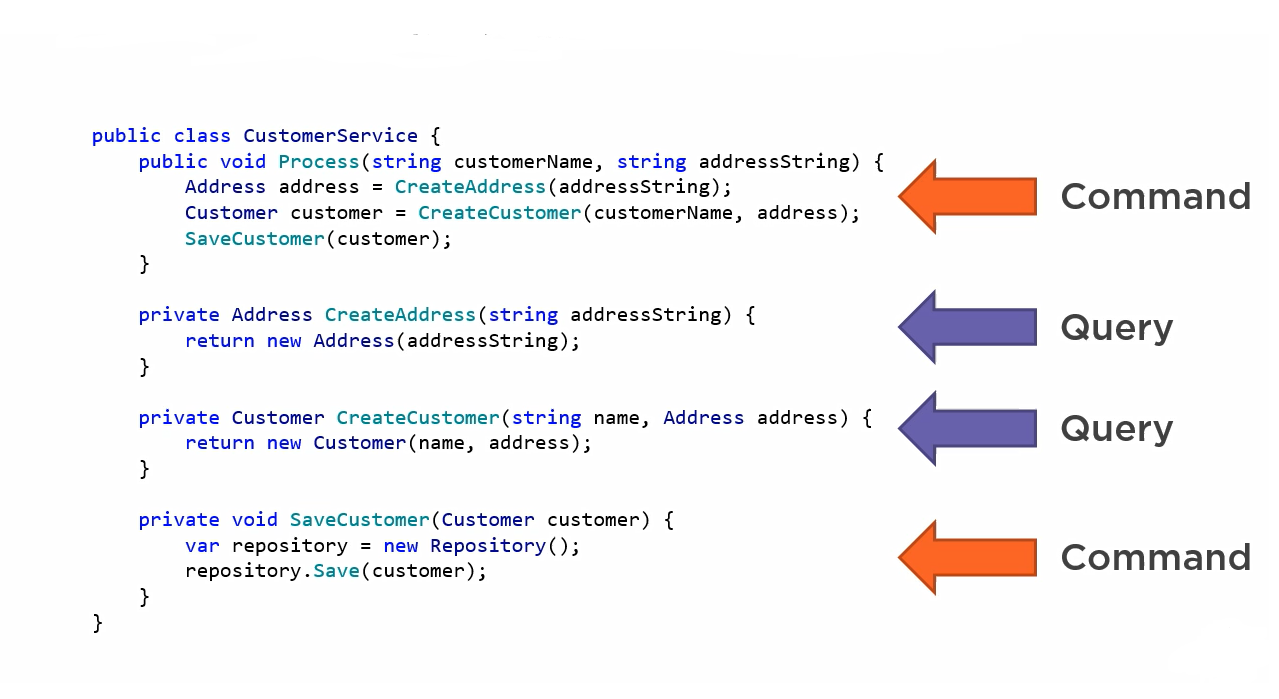

Consider the example below, where I separated the Command and Query components:

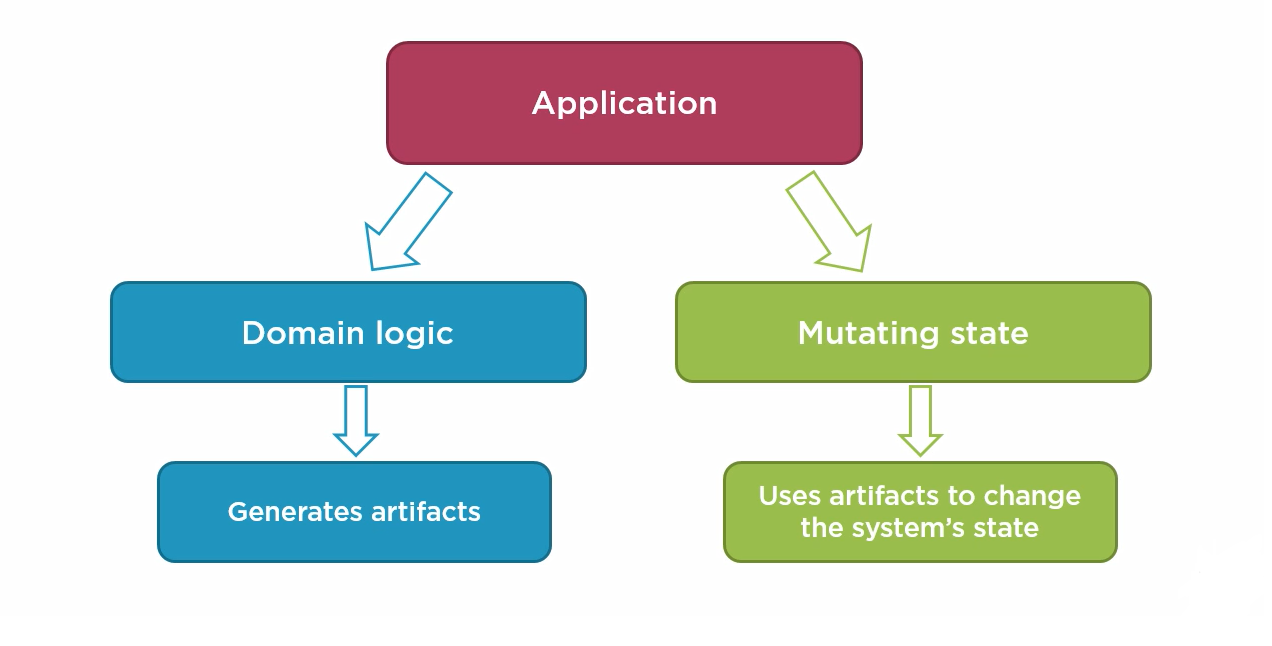

An application can generally be divided into two parts:

- Business Logic: The part of the application that implements the business rules, which should be immutable and produce outputs.

- Mutable Shell: The part that uses the produced output to store or manage system state.

Essentially, the core of the application is Immutable, taking inputs and generating the necessary outputs, while all these processes occur within a Mutable Shell, which is responsible for interacting with the system’s state.

For the aforementioned concepts, I have prepared a simple example: a queue management system. The system stores/retrieves appointments (mutable) and the logic for managing appointment schedules can be implemented in an immutable fashion.

This code has been implemented both functionally and non-functionally, which helps us clearly understand the difference before and after applying functional programming techniques.

For better readability and access to the code, I have uploaded it on GitHub. You can check the source code here. The example includes all the concepts discussed in this post.

I hope the topics covered regarding functional programming have provided a fresh perspective on the code we write. In future posts, I will address topics like exception management, working with null values, and more.