Functional Programming - part 4

Handling Exceptions in Functional Programming

If you haven’t read the previous parts of this Functional Programming series yet, I highly recommend reading the following articles first: Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 before continuing. In this section, we will examine the impact of exceptions on code and present a functional approach to handle them.

Exceptions and Code Readability

Consider the following code: A regular action in ASP.Net MVC that receives a name and creates an employee.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public ActionResult CreateEmployee(string name) {

try {

ValidateName(name);

// continue with other code

return View("Successfully registered");

}

catch (ValidationException ex) {

return View("Error", ex.Message);

}

}

private void ValidateName(string name) {

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(name))

throw new ValidationException("Name cannot be empty");

if (name.Length > 100)

throw new ValidationException("Name cannot be longer than 100 characters");

}

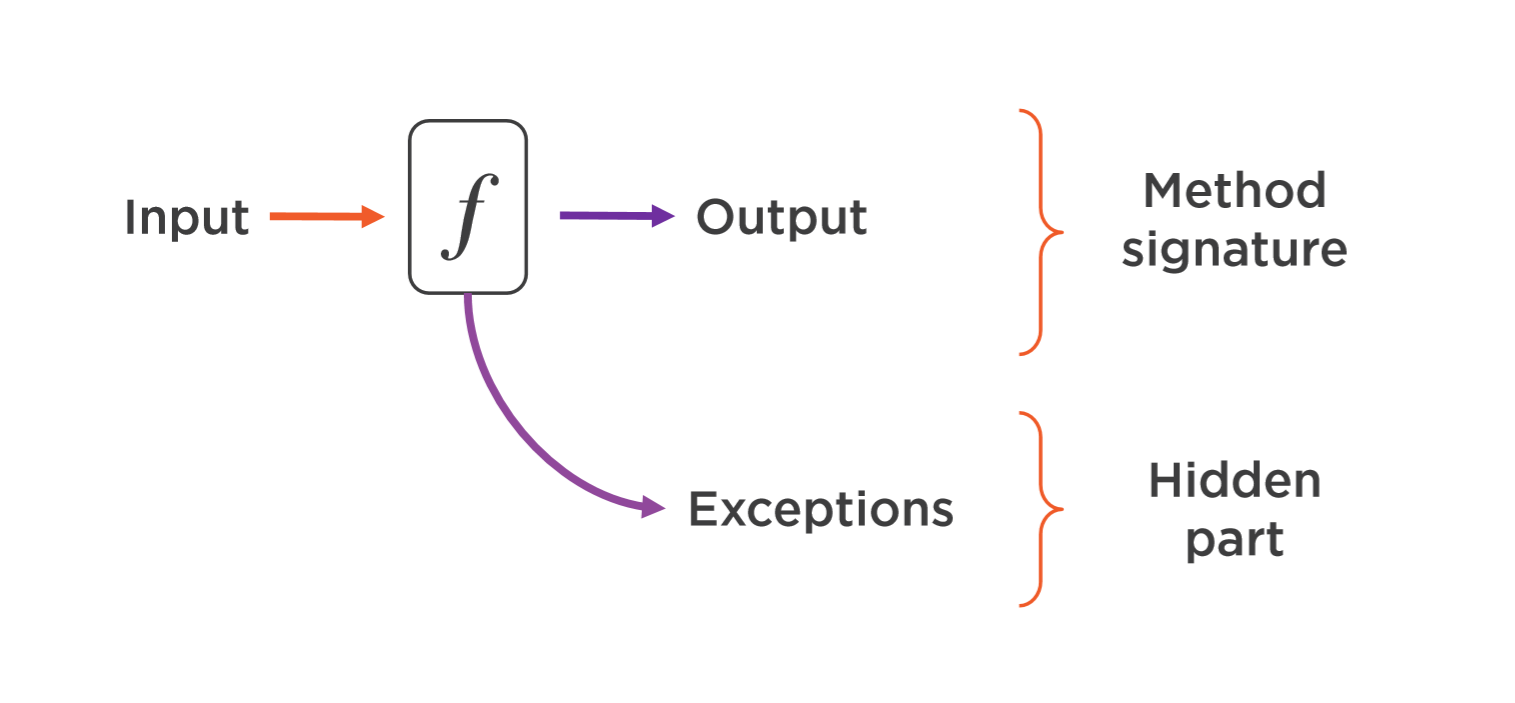

In this snippet, the ValidateName method throws an exception if the input is invalid, and the try/catch block catches this exception and shows an appropriate error message to the user. So far, everything seems fine, and this is a familiar pattern in many projects. However, the ValidateName method is not honest. As we discussed earlier about honesty, you can’t tell what this method actually does or what type of output it will produce just by looking at its signature.

In functional programming, we aim for clarity. Just like mathematical functions, we expect methods to behave predictably based on their signatures. Using exceptions in this case can obscure the flow of the program, much like the old GOTO statement. Before structured programming, GOTO was often used, which made understanding the program flow much more complex. Similarly, using exceptions to control program flow can create even more confusion, as exceptions can propagate across different layers of the code.

A Better Approach: Refactoring the Code

What if we refactor the code to avoid exceptions for control flow? Here’s an example of how you could rewrite the above code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public ActionResult CreateEmployee(string name) {

string error = ValidateName(name);

if (error != string.Empty)

return View("Error", error);

// continue with other code

return View("Successfully registered");

}

private string ValidateName(string name) {

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(name))

return "Name cannot be empty";

if (name.Length > 100)

return "Name cannot be longer than 100 characters";

return string.Empty;

}

In this refactored version, we’ve made ValidateName more like a mathematical function that just returns a value based on the input, making it predictable and transparent. This approach adheres to the principles of honesty and ensures that the method does exactly what its signature suggests, with no hidden behavior. This is a step toward making our code clearer and easier to follow, but keep in mind that this is not our final solution—please continue reading.

When to Use Exceptions

So, given everything we’ve discussed about exceptions, when should we actually use them?

- Exceptions are for exceptional cases.

- Exceptions are for situations that truly represent bugs in the program.

- We should never expect an exception to occur unless it’s truly exceptional.

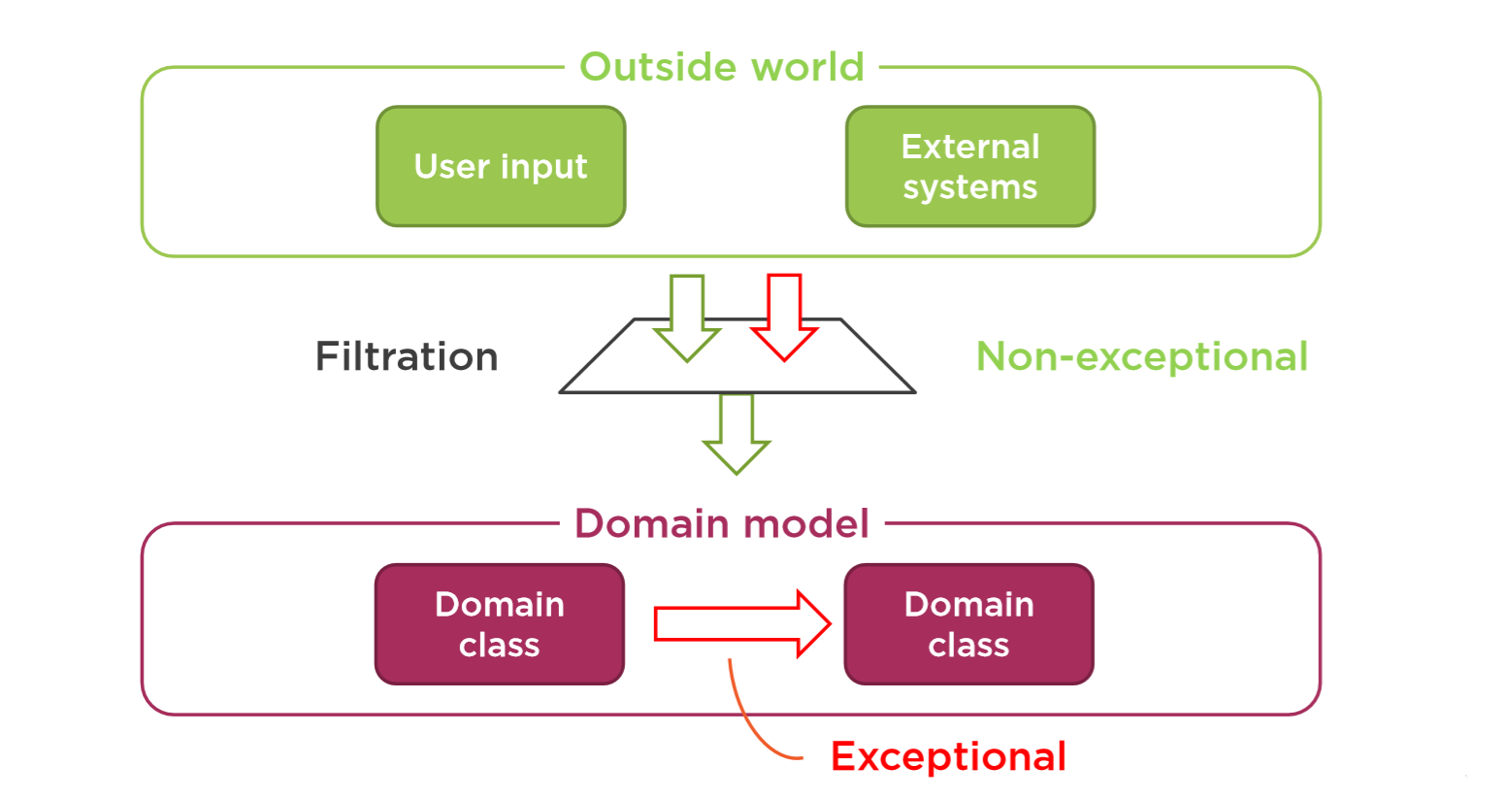

Regarding the third point: when validating user input (like form data), it’s normal to expect incorrect or missing data. This should not be treated as an exceptional case, but rather as a regular condition that needs handling. Consider the following architecture:

The data coming to our API should always go through some kind of validation or filtering, and since we expect invalid data from time to time, it would be incorrect to treat that as an exception. However, when the data exchange happens between different domains and the data is invalid, that should be treated as an exception. Consider this example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public ActionResult UpdateEmployee(int employeeId, string name) {

string error = ValidateName(name);

if (error != string.Empty)

return View("Error", error);

Employee employee = GetEmployee(employeeId);

employee.UpdateName(name);

}

public class Employee {

public void UpdateName(string name){

if (name == null)

throw new ArgumentNullException();

// continue with other code

}

}

In the code above, the UpdateName method expects that the name will never be null, so we’re checking for null again inside the method. If we throw an exception when the name is null, we are rechecking the same condition that was already validated in the controller. This kind of redundant checking in multiple layers is commonly referred to as a guard clause and is often considered a code contract among developers.

As we mentioned earlier, if a name is null, it indicates a bug in the software, and thus it is an exception.

Fail Fast Concept

Up until now, we’ve seen that exceptions should only be used for exceptional circumstances. But how do we handle them in such cases? This leads us to the concept of Fail Fast. The Fail Fast principle suggests:

- Stop the current operation immediately when an exception occurs.

- Following this principle leads to a more stable software.

Let’s contrast this with the opposite approach, Fail Silently. Consider the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public void ProcessItems(List<Item> items) {

foreach (Item item in items) {

try {

Process(item);

}

catch (Exception ex) {

Logger.Log(ex);

}

}

}

At first glance, this might seem like a stable application that handles errors gracefully. However, this is not the case. By logging the error silently, the programmer might miss critical failures, leading to corrupted data or inconsistent behavior.

There’s no safeguard preventing operations from continuing when they shouldn’t. As we discussed earlier, an unexpected condition is actually a bug, and there’s no benefit in ignoring the issue without resolving it.

In summary, the most important benefits of Fail Fast are:

- The path to identifying errors is clearer.

- The software becomes more stable.

- Data integrity is guaranteed.

Where to Catch Exceptions?

You should catch exceptions in the following situations:

- Logging: Log the exception for further inspection.

- Stop the operation: If continuing might cause further issues.

- Never put logic inside the catch block: Avoid placing logic that could obscure the true cause of the error.

Another case for handling exceptions occurs when using third-party libraries. For example, in Entity Framework (EF), you might encounter exceptions due to database connection issues. Here’s how to handle them:

- Catch exceptions at the lowest possible level in your code.

- Catch only specific exceptions that you know how to handle.

This means you should avoid catching generic exceptions. Instead, catch specific exceptions in the catch block.

Handling Exceptions Properly: A Practical Example

Here’s a real-world example of handling exceptions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

public void CreateCustomer(string name) {

Customer customer = new Customer(name);

bool result = SaveCustomer(customer);

if (!result) {

MessageBox.Show("Error connecting to the database. Please try again later.");

}

}

private bool SaveCustomer(Customer customer) {

try {

using (MyContext context = new MyContext()) {

context.Customers.Add(customer);

context.SaveChanges();

}

return true;

}

catch (DbUpdateException ex) {

if (ex.Message == "Unable to open the DB connection")

return false;

else

throw;

}

}

In this code, when a DbUpdateException occurs, we return false. But this solution is not very clear or honest. Returning a bool doesn’t provide sufficient information about the failure. Instead, we can return a more structured response using a custom result type. Here’s how we could refactor this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

private Result SaveCustomer(Customer customer) {

try {

using (var context = new MyContext()) {

context.Customers.Add(customer);

context.SaveChanges();

}

return Result.Ok();

}

catch (DbUpdateException ex) {

if (ex.Message == "Unable to open the DB connection")

return Result.Fail(ErrorType.DatabaseIsOffline);

if (ex.Message.Contains("IX_Customer_Name"))

return Result.Fail(ErrorType.CustomerAlreadyExists);

throw;

}

}

In other words, with this approach, we can ensure whether an operation succeeded or failed, and return the result along with the reason for failure.

If we look at the signatures of the methods below, we can categorize them according to CQS (Command Query Separation).

As an example, I’ve provided an implementation of this class here:

Certainly, we can have better implementations of this class, and I would be happy if you share your thoughts with me.

I hope this section and the discussions about exceptions have provided a new perspective on your code. In the continuation of this series, we will dive deeper into the concepts of functional programming paradigms.

Conclusion

I hope this post has given you a fresh perspective on handling exceptions and their impact on code readability. We’ve explored the principles of honesty and fail-fast and demonstrated how to refactor your code to avoid using exceptions for flow control. In the next parts of this series, we will delve deeper into more advanced functional programming concepts. Let me know your thoughts or suggestions!